'I wish I could be like a bird in the sky'

Dementia has relinquished its grip on my mother. She is free. In my grief, it helps to imagine her dancing with my father to Nina Simone somewhere on that heavenly dance floor, returned to herself.

We sit in the lush garden of the memory care facility, Mom in her wheelchair, covered in a crocheted blanket made by a hospice volunteer. It is Friday, April 12, my 64th birthday. A clear blue sky, a slight breeze waving the palms. I hold up a soft chocolate fudge cookie.

“A birthday cookie,” I tell her. “It’s my birthday. Would you like some?”

She smiles, nods. “Cookie,” she says.

She takes small bites and chews slowly. I wait, anxious to see if she can swallow and she does. I hold a cup of cranberry juice, her favorite, to her lips and she sips from the straw. She accepts another piece of cookie.

“I love you,” I say.

She turns to me. I can see her mouth wanting to say it back to me but she cannot form the words. “L…lo…” she says and then falters and smiles again. I blink back tears. It is enough.

We sit for awhile longer as I hold her hand. The breeze picks up. Her nose is runny and I wipe it with a tissue, zip her sweatshirt up and put on the hood. I worry she will get chilled. She is so very frail. I wheel her back inside.

That morning the hospice nurse had met with me in the director’s office to tell me that Mom was at end of-life, “transitioning,” a comforting phrase. It doesn’t have the bluntness of “dying”; it allows my emotions to catch up. “She is not eating or drinking very much,” the nurse says. She is now getting morphine for her pain. I see it when I enter her room and lay my hand on her shoulder. She winces. Everything seems to hurt.

But when she sees me, she rallies. When I ask if she wants to go outside on this beautiful day, my birthday, she smiles and says “Yeah.” She cries out in pain as the nurse and I lift her onto her wheelchair. “Be careful,” she says. But she is calm and content as we sit together and she eats the cookie.

This is a gift, I think later. She rallied for me, as many people do in the days before their death. I lay my head gently next to hers. “Mommy,” I tell her. “I love you.”

Her skin is warm, damp and salty the next morning when I lean down to kiss her cheek. Today, Saturday, she does not want to get out of bed. She accepts a few bites of chocolate pudding. She tells my sister, sitting beside her, “I love you.” She smiles at us, squeezes our hands. But her words are few: a “thank you” for the offer of a cup of juice raised to her lips, a “sure” in response when we ask if she is sure she has had enough to drink.

We play her favorite music, Tony Bennet, Frank Sinatra, Nina Simone. Nina’s vocals soar in “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free:”

Well, I wish I could be

Like a bird in the sky

How sweet it would be

If I found I could flyOh, I’d soar to the sun

And look down at the sea

Then I’d sing ’cause I’d knowI’d know how it feels to be free

I tell her the story she has told me and my siblings and her grandchildren so many times: about the night she met my father, how he invited her to walk down the street to hear Nina sing in a bar in Greenwich Village. I know my father is waiting to dance with her again. He has been waiting several years now.

I read to her from The Bobbsey Twins by Laura Lee Hope, a childhood favorite. I ordered a copy for her 86th birthday last year, so she could once again hear the tales of the two fraternal sets of twins, Freddie and Flossie, Nan and Bert. I read from “Lost and Found.” Six-year-old Freddie falls asleep in the department store after wandering away from his mother, discovered by the night watchman.

“When Freddie woke up all was very, very dark around him. At first he thought he was at home, and he called out for somebody to pull up the curtain that he might see. But nobody answered him and all he heard was a strange purring, close to his ear. He put up his hand and touched the little black kitten which was lying close to his face.”

I caress a soft black stuffed kitten against Mom’s cheek. I think of her beloved cat Pablo Picasso who “crossed the rainbow bridge,” as Mom called it, a few years ago. He is waiting, too.

“The darkness did not please him, and he was glad to have the black kitten for a companion.” Later, Freddie calls out in the darkness: “Mamma! Mamma! Mamma, where are you?” and receives no answer. He hugs the kitten tight. “They have all gone home and left me here alone…He knew the night was generally very long and he did wish to remain in the big lonely building until morning.”

I play her another favorite song, James Taylor’s “Sweet Baby James.”

Goodnight, you moonlight ladies

Rockabye, sweet baby James

Deep greens and blues are the colors I choose

Won't you let me go down in my dreams?

And rockabye, sweet baby James

That evening, I leave her to walk the beach. I try to find my center, to soothe myself. I sense what is coming. I can’t bear to be away from her but I need to sleep at home in my own bed. I call my brother who lives a few states away. I can’t give an answer as to how much time is left, the unanswerable question. No one can. It is one of the hardest things about death, particularly this “long goodbye” that is dementia.

A hospice social worker tells me with compassion, “She is on her journey. It is so much harder for the family, the not knowing.” Sitting in my kitchen, I pick at the plate of food I’ve prepared. When she can’t eat, this feels like a betrayal, an indulgence. She would want me to eat, I know, but the food is tasteless. I hear children’s voices outside, a car door slamming. Life continues on, as it does.

Sunday morning. The nurse at the memory care calls me at eight-thirty. Mom has had her dose of morphine. She is resting comfortably but refused breakfast and juice. I quickly pack books to read to her, my journal, and a phone charger, my heart racing, panicked. Not ready, I think, after a restless night.

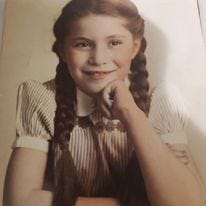

Lying in bed, she opens her eyes to look at me but her gaze is unfocused. I see she is trying to smile. She reaches for my hand, squeezes. “I love you,” I say, leaning close. I cannot say it enough. I read to her a passage from Mark Nepo’s Book of Awakening, in which he writes, “Acceptance is the key to receiving grace.” This is intended for me, I realize. My siblings and I are struggling to accept that the end is near. My sister and I take turns holding a sponge stick moistened with water to her lips, encourage her to drink. Her lips are pursed and she firmly pushes my hand away. We need to honor her wish. She is not thirsty. Maybe she is dreaming of her horse, King, the one she loved to ride, her long thick hair braided, a mane that swung in the wind just as King’s did.

She puts her hand up to her head, tugs at her hair, and at one point waves her hand over her eyes. She pulls at her blanket. It is painful to see her agitation. She is very warm and her heartbeat is rapid. Her small thin chest heaves with every labored breath. Her hands have taken on that bluish hue we remember from when our father was in hospice. We call for the nurse who gives her a dose of morphine and then, as she continues to struggle to breathe, another small dose to help with the shortness of breath—to hopefully give her and us a little more time. Her heartbeat slows. But her breaths start to pause, unbearable seconds between the breaths. The young nurse, her eyes full of compassion, her hand on my mother’s head, tells us, “It’s not long now.”

My sister is sobbing, holding my mother’s hand. “No, no, I’m not ready! Don’t go yet! Please, please wait.” I understand her sorrow and her desperation, my baby sister. But there is something I want to be brave enough to say. I lean close to Mom’s ear and put my hand on her cheek. “It’s okay to let go, Mom,” I say through my tears. “We love you. You can go now.”

She takes her last breath. She is still. She is at peace. My sister cries and we hold each other. We had wanted more time. You always do. Yet this has been the unexpected gift of the long goodbye of dementia; I have been preparing myself for a long time. And while so much was lost to her and to us as dementia tightened its grip, this never changed: she loved us right until the end, this incredible woman who taught us to love so well.

We have not eaten all day. We go to a pizza restaurant and a sweet young man with Down’s Syndrome smiles with delight, greeting us as we pass his table. He gets up and beams at me as he walks over. I stretch out my hand and he kisses it. His father smiles indulgently. Love. It’s all around us. We need to stay open to it.

Later, when the calls have been made to my brother and his family, to my daughters, and my sister has gone home, I drive to the beach for the sunset. I have cried a little but mostly I feel numb and dazed. I speak briefly to my friend and mix it up, say “I feel dumb.” But it’s true. I feel dumbstruck. Unable to speak what is on my heart. I need to be alone. I feel the desire to go inwards.

I pull aside as an ambulance with flashing lights speeds by. I carry my chair down to the edge of the Gulf. I sit and watch children playing in the surf. A memory comes. My mother standing in the waves of the Atlantic Ocean, holding my daughters’ hands as they skip the waves together. I let the tears I’ve been holding back flow as the sky turns orange. I listen to Alexi Murdoch’s “Orange Sky.”

Well I had a dream

I stood beneath an orange sky

Yes I had a dreamBut sister you know I'm so weary

And you know sister

My heart’s been broken

Sometimes, sometimes

My mind is too strong to carry on

Too strong to carry onWhen I am alone

When I've thrown off the weight of this crazy stone

When I've lost all care for the things I own

That's when I miss you, that's when I miss you, that's when I miss you

You who are my home

You who are my home

She was my home.

It is on the drive back to my apartment that I break wide open, sobbing, as I listen to “Memory” from my mother’s favorite musical, “Cats,” that we saw on Broadway years ago with her oldest granddaughter—one of several performances she enjoyed. The last stanza pierces me:

Touch me, it's so easy to leave me

All alone with the memory

Of my days in the sun

If you touch me, you'll understand what happiness is

Look, a new day has begun

“Oh Mommy, I’m so sorry, so sorry,” I cry out, my hands clenching the steering wheel. If I had known I had only two weeks with her after my return from a month of travel in March, I would not have left her side. I go to that place where I castigate myself for leaving her “all alone with the memory of my days in the sun.”

I am also crying for being left alone, orphaned. The little girl in me is bereft. I whisper to her, “You are a good girl, you have done nothing wrong. It’s okay to be sad, to cry.”

No matter how old you are, losing a loving mother is among the worst kind of losses.

But then I remind myself. It was dementia that stole her memories. We—her loving family—were her memory keepers. And when we touched her, held her hand, we did understand what happiness was. We did our best to usher her into a new day.

Now we have to walk into our own days without her. It will take time. At age 64, I know this kind of loss, as so many of us do. My father. My best friend. My loving Swedish in-laws. But this loss. It cuts deeper. I call the funeral home, tearful. I beg them to call me as soon as they can. When a kind woman calls back and expresses her condolences I say, “I just need to know my mother’s body is safe and sound.”

“Yes, she has passed into our care,” she says.

Today my siblings and I will make funeral arrangements, talk about plans for a celebration of life. Mom would have wanted a joyous party in her memory and that is what we will do. Dance to Sinatra’s “My Way” and Nina Simone’s “I Put a Spell on You,” and Johnny Mathis’ “Misty:”

Look at me,

I'm as helpless as a kitten up a tree

And I feel like I'm clinging to a cloud

I can't understand,

I get misty just holding your hand.

I remember her wish to have her ashes scattered to the winds, to the four corners of the earth, just as we did with my father—to be, as Nina sings, “as free as a bird in the sky.”

For now, we hold each other in love and tenderness. The time for dancing will come. And she and my father will be with us, leading the way.

Question for the comments: In times of grief and loss, what has given you the most comfort? How have celebrations of life been meaningful to you? My heart is open to whatever you wish to share.

Absolutely stunning. The details. Her hoodie sweatshirt, her peaceful exit, her husband awaiting her.

Ah, I hadn’t thought of it that way. Thank you. I found it comforting during my mother’s death and funeral that many people reached out to us. I’m sure it will be the same for you and your family. You know how loved she was and it will be wonderful to hear from people who loved her. You will miss your mother daily of course but also at odd times. It’s a discovery living without someone. Thinking of you!