Even in the locked world of dementia, the power of storytelling survives

There are so many ways to keep our stories alive, even as memory retreats.

Some of my earliest memories are sitting on my mother’s lap as she read to me from Curious George Learns the Alphabet or Green Eggs and Ham or Syd Hoff’s Grizzwold series. She opened up the magic kingdom of books for me (a magic kingdom requiring no trip to Disney World). Suddenly entire worlds were in my little hands, filling my imagination. As soon as I could read myself, that’s all I wanted to do. My mother told me that I would refuse to go out and play with the neighborhood kids, preferring to stay in my room and read.

I am my mother’s daughter in so many ways, but especially in this respect. One afternoon in spring of 2021, she recalled for me the most beloved books of her childhood. That included The Bobbsey Twins. “I can even remember their names,” she said, her face lighting up. “The younger ones were Flossie and Freddie. And the older ones were Bert and Nan.”

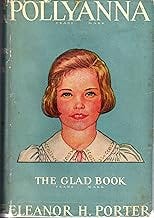

She also loved Pollyanna, with its cheerful subtitle: The Glad Book. “I remember thinking how it was impossible to be like Pollyanna but that also the world needed more Pollyannas,” Mom said.

For those unfamiliar with this classic, the title character has an unfailingly optimistic outlook and today a positivity bias is often referred to as the Pollyanna Principle—the tendency for people to remember pleasant things rather than the unpleasant ones.

Today, Mom is no longer reading her beloved books. She hasn’t read a novel for about a year now. There was a period when she held a book in her lap but was too tired to open it. It seemed to give her comfort nonetheless. Now she no longer asks to go to the library, one of her favorite places on earth. A recent trip to a favorite local bookstore seemed to only fill her with confusion and she retreated to an armchair to wait for me to finish browsing the shelves.

It breaks my heart, this loss among so many others. And yet, I sit with her now and I think, “It wasn’t so impossible after all, Mom, for you to be Pollyanna.” When we chat, what surfaces are the pleasant memories, the things that gladden her heart: the feel of her horse King under her thighs as a young girl, the taste of strawberry ice cream on a hot summer day, the way she and my father met at a bar in Greenwich Village in 1959 and then sauntered down the street to listen to Nina Simone perform.

We look for stories to shield us from an unwelcome truth

I am so glad for the conversations Mom and I had in 2021. Even after a second test that year confirmed her cognitive decline was “moderate,” no longer “mild,” I tried to convince myself it wouldn’t get worse, that perhaps she would avoid the specter of full-blown dementia.

As I wrote in my earlier post on this topic, Hello to the Long Goodbye, there were no definitive answers to questions like how much would change for Mom and how quickly. As so many families do, we adjusted to the changes little by little and hoped for the best. These are the stories we tell ourselves to get through the day. A journalist, I noticed an unusual tendency in myself not to want to dig too deep into the dementia literature, to be faced with the reality that about one-third of people diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) will develop dementia due to Alzheimer’s within five years. While I knew the neuropsychologist had diagnosed Mom, then 84, with vascular dementia, I didn’t fully understand what that could mean for her and a persistent part of me didn’t want to know.

Instead, I spent every moment I could with her, capturing on video her memories of the past to share with her grandchildren, inviting our book club to my home for our first post-pandemic gathering, taking my tree-hugging Mom on walks in nature. On those walks, she was unsteady and she tired easily, sat down at every bench and asked to leave fifteen minutes into the excursion. She was dividing her time between my sister’s home and my home, as we live close to one another. The moving between houses added to her confusion, I realized, but my sister and I both cherished time with Mom and we sensed it was fleeting, even if we didn’t talk about it.

While I watched my mother’s decline, feeling increasingly helpless, in the back of my mind a worry began to form. Studies have found that if you have a close relative who has been diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, your risk of developing the disease increases by about 30%. Was this to be my fate, too? Or that of my siblings? Could we do anything about it?

A silver lining for children of parents with dementia—or spouses of those with dementia—is that more than the general population, we are painfully aware of how devastating this illness is. We watch it unfold every day in our loved ones. That should give us plenty of incentive to stay on top of our own cognitive health through regular evaluations to detect changes to the brain.

Yet a study that came out last week found that over 90% of Americans with MCI remain undiagnosed. Also deeply troubling was that of the over more than 200,000 primary care physicians surveyed, all of whom see patients 65 and older, 99% are underdiagnosing MCI.

Good tests for MCI exist, and take approximately 15 minutes to administer. And it is all the more important now that the first Alzheimer’s drug to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is available, called lecanemab, or Leqembi. The drug can slow down the disease’s progression but only if used in the early stages of the condition. At 63, I have not noticed any signs of cognitive decline in myself. But I know that I will be asking for a MCI test just as soon as I do.

My mother is no longer able to read her beloved childhood books, but in the hope of bringing back warm Pollyannish memories, a collection of Bobbsey Twins and Pollyanna books is on its way. It will be my turn to read to her.

If you’d like me to read to YOU, I am now recording audio versions of each of my newsletters for paid subscribers, here in my little home podcast studio:-), sent as a separate email. And now, for some music….

3 Songs for 3D

Divorce

Janis Ian, “Between the Lines.” In the years of coming to recognize Mom’s decline, it was easy to stay busy and not pay attention to what was happening in my marriage, “between the lines of what we need and what we'll take/There's never much to talk about or say aloud/ But say it anyway/ Of holidays and yesterdays, and broken dreams That somehow slipped away.”

Dementia

Kermit, “The Rainbow Connection.” My mother’s very favorite song and one I can’t listen to without tears in my eyes. “What’s so amazing that keeps us stargazing and what do we think we might see? Someday we’ll find it, the rainbow connection, the lovers, the dreamers and me.”

Destiny

Bela Fleck, Abigail Washburn, “If I Could Talk to a Younger Me.”

If I could talk to a younger me

I'd tell me to go slow

This time on Earth it moves so fast

And when it's gone, it's gone

I am thinking of your mum lots after reading that. I didn't know her very well but the few times we met she was so positive, funny and kind. And I think those genes have definitely been passed down to you. What a wonderful gift.

Another beautiful and poignant writing and one so relatable. I haven't thought of the Bobbsey Twins in years! Thank you for sharing more insight with your mom's journey. I hang onto every morsel as I recognize all too well the progressive events and the wave of emotions that come along with the decline. I am learning to feel grateful for those beautiful moments and I am so inspired by your writings to do more to capture these precious times and memories.