Today I have the honor of featuring a beautiful essay from my first guest columnist, my daughter Marielle. There is so much here to feed your own clarity, connection, community and creativity, inspired by Rumi, and I am excited for all my subscribers to enjoy this journey.

By Marielle Velander

“Do you think you will ever see her again?” my boyfriend asked me across the table at a late-night diner in Turkey’s capital Ankara. He was speaking of my best friend, now an angel, as her mother and I refer to her. It prompted me to think more deeply about my spirituality - and the deeply spiritual nature of a meaningful friendship.

What happens after you die? For many years, my favorite quote about the afterlife (and love—two deeply connected concepts in my view) has been this fragment from a poem by Rumi:

Love is: to fly toward a secret sky, to watch a hundred veils fall.

First to take a step without feet; then to let go of life.

Is that what my best friend did when she left us suddenly from the ruined confines of a car she loved?

I also think of this quote as an inspiration to travel, to see new places and seek different perspectives; an invitation to explore the unknown.

That is perhaps why I found myself wrapping up a year-long backpacking trip (for which the seeds started on my very last trip with her over 2 years ago) on a pilgrimage to the town where Rumi, this mystical poet from the 13th century, spent most of his life.

Rumi was born in Balkh, in present day Afghanistan, but as a child he migrated with his family to Konya, current day Turkey. It is in Konya, at the time the capital of the Seljuk empire, where his family settled and he began his studies to become an Islamic scholar. It is also the city where he made a friend—and it’s this friendship that would turn him into a mystic.

In his 30s, Rumi encountered a wandering dervish named Shams al-Tabriz. Shams became a teacher and a master to Rumi, in addition to a dear friend. It was to Rumi’s great distress that suddenly and mysteriously Shams al-Tabriz disappeared.

Some say he was murdered for his influence on Rumi’s ideas, others that he simply wandered off one day, as wandering dervishes are wont to do. A waiter at a restaurant we ate at in Konya proffered that Shams was just a figment of Rumi’s imagination, perhaps the voice of God. All we know for sure is that after Shams disappeared, Rumi wrote his most ambitious and influential work yet, the Masnavi. Through Rumi, Shams’ teachings and values lived on and still reverberate to this day.

Based on my own experience, the story of Rumi losing his friend resonated. What resonates perhaps even more so is also the enduring lessons and deepening spirituality that come from losing a dear friend.

On my journey through grief, and on this year-long sabbatical, I have found a few things that inspire my clarity, connection, community and creativity. Some are tied up with my trip to Rumi’s tomb and the sacred ceremonies he inspired in his chosen home. Others ripple out beyond Konya.

Clarity

“First to take a step without feet…”

The first time I ran off a cliff, I was on the wild coast of Chile.

Don’t worry, I had an experienced pilot and parachute attached to me. Paragliding was my first experience of truly putting that Rumi quote to practice. I started off my sabbatical year volunteering to run penguin and sand boarding tours near Valparaiso. For lunch we would always stop at a paragliding spot with a spectacular view of the dramatic coastline, perched on one of those steep cliffs dropping into the Pacific ocean. After seeing people of all ages take flight, it was finally my turn. The winds were good, not too strong nor too weak, and the skies were clear. I signed off a waiver and got equipped. The pilot strapped behind me shouted “run” and suddenly, I took those weightless steps and we began to soar.

Something I expected to be exhilarating was actually deeply meditative and peaceful. All you could hear were those winds in our sky sails as we glided over deep hidden coves, that only seabirds and marine creatures could reach. When we landed the song “Seabird” echoed in my ears. I had actually felt like a bird and it felt revitalizing…and a step closer to my best friend.

Nearly a year later, on the other side of the world, I had the opportunity to paraglide a second time. This time, though, I had someone to share the experience with, a love I feel my best friend spiritually placed in my path only a few days after that first paragliding experience. This time we were not flying over a South American coastline, but rather an ancient city and blindingly white travertine pools in the mountains of Anatolia.

My boyfriend had the same reaction as I did. Beforehand he was mentally bracing himself for the adrenaline rush of something athletic. As he approached me after landing he said “That was so relaxing. I need to have my parents do this.”

Why do we find paragliding so calming? I think that birds-eye view gives a striking clarity, both in terms of how small our lives are and how vast the world is. It also grants insight into how other species, less troubled by our everyday human complications, may see the world. Flying over an ancient city gave a deeper perspective, into the vast vestiges of time and what remains after a civilization is gone.

I encourage you at some point to try paragliding. It’s deeply therapeutic, and allows you to live Rumi’s words in an entirely new way.

“To let go of life…”

Connection

Bashful blossom! What a wispy thing you are,

And wheeling constantly to face the sun…

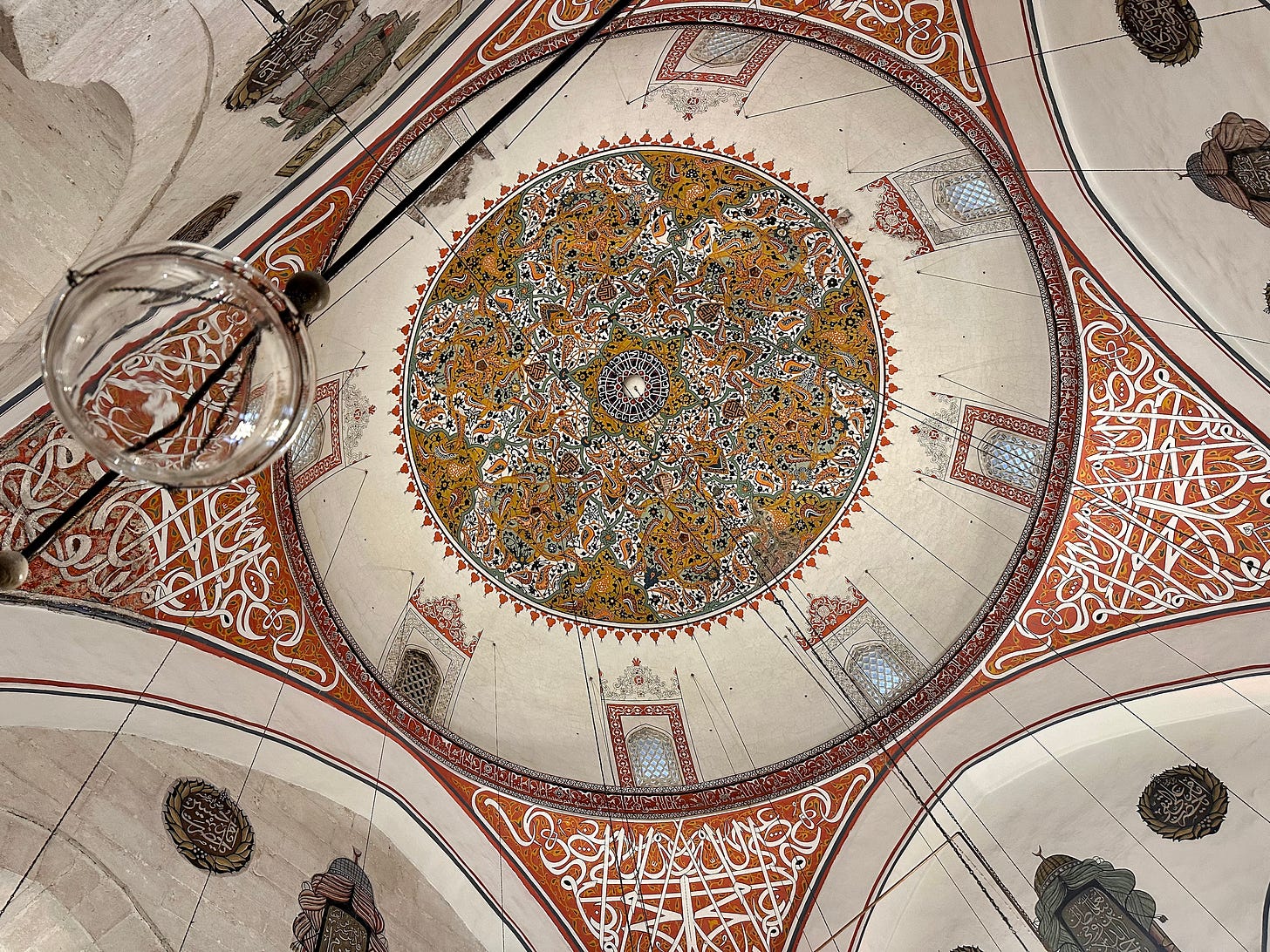

Speaking of seemingly transcendental experience, one of the most beautiful rituals that has survived since Rumi’s time is that of the “sema”, known in the West as the “whirling dervishes”. This ceremony is deeply symbolic, and should not be approached as a form of entertainment but as a form of worship and sacred spiritual practice.

We attended the ceremony in Konya, where it takes place every Saturday night just down the road from Mevlana Rumi’s tomb, in a large concert hall particularly built for this purpose. The ceremony started with a reading of Rumi’s poems in the original Persian. A haunting voice began to sing in Arabic, as musicians began to play instruments that have been used since Rumi’s era. Eventually, the wailing reed instrument “ney” was the only sound that echoed over the dark concert hall as the dervishes huddled under dark cloaks on the corner of the stage. As the music crescendoed, they rose up and dropped their cloaks, and began one by one to approach the turbaned master that stood tall across from the musicians. That is when they began to twirl.

The whirling dervishes are at the heart of this ceremony and everything about them is imbued with spiritual meaning. They wear tall hats meant to symbolize their tomb stones and white gowns similar to funeral shrouds, to mark the death of their ego. As they turn, the gowns spreading out around them in bright white orbs, they lift one palm up to receive divine love, and hold their other palm facing down to spread that love.

Dancers of all ages took part, albeit only males, and they spun in seven rounds, to mark each of Rumi’s principles. These are:

In generosity and helping others: be like a river.

In compassion and grace: be like the sun.

In concealing others’ faults: be like the night.

In anger and fury: be like the dead.

In modesty and humility: be like earth.

In tolerance: be like the sea.

Either appear as you are or be as you appear.

After the ceremony, which was moving and inspiring even for someone so removed from this culture and spiritual belief system, we went downstairs to explore the market with the instruments and artworks sold by local artisans. I was drawn to one piece of art that echoed Rumi’s 7th principle, because it is the one I found the hardest to interpret. What did he mean by “appear as you are or be as you appear”?

My boyfriend and I discussed it with the three generations of artists at one stall, and settled on the understanding that it captures the importance of being true to yourself in how you present yourself to the world. Essentially, live your values. (Oh and in case you were wondering, we bought the piece of art.)

That brings me to the point of connection. As I observed the dancers twirling, I felt disconnected from this time period, lost in the whirling of the world for centuries. Then I looked around at the crowd; foreigners from a range of places and of course locals from all over Turkey were watching. We were connected in that moment, both with our contemporaries in the room and all those people who had been as they appeared, in this same ceremony in this city for hundreds of years.

Community

The wise men tell us that we take these tunes

From the turning of celestial spheres

These sounds are revolutions of the skies

Which man composes with his lyre and throat

On the topic of music, it is in its capacity as a connector that it has become a source of community for me. Wherever I travel in the world, music breaks down all the barriers, whether they are cultural, linguistic, a matter of age or gender. Music deeply familiar to me pops up in the most unexpected places.

Like the first date with my now partner, in far-off (for me) Valparaíso, Chile, where amid a classical tango concert erupted a traditional waltz I knew well through my Swedish grandparents. Like the salsa class I attended while solo-traveling in Cali, Colombia, that had guest teachers from Cuba to show a version of salsa I spent a year studying in college in the US. Like the farm in Montenegro where, after a hard day’s work of harvesting sweet potatoes I ended up singing a favorite Amy Winehouse song with my Chilean boyfriend and a French-Australian couple.

Music was also how I first got to know my best friend. She was in an acapella group in college called “emocapella” that only sang the so-called “emo songs” that I had been bullied for liking in elementary school. It felt so validating finding someone who liked the same music at such a vulnerable and uncertain time as freshman year of college. This Bolivian girl, through many karaoke nights and jam sessions, became a sister to me. So I have music to thank for giving me the community that, even in spirit form, brightens my darkest days.

Creativity

Presence

It was you in that

Orb emanating not

Words but waves

Of the yearning we learned

And unlearned in the grief

That calls each ocean

Unto itself

A shard of sea glass

Lost in the swell

Polished in time’s shell

As this orb turns in

The light of the love

We thought we forgot

But never turned away

I wrote this poem on a beach in southern Turkey while watching the sunset you see below. Earlier that day we had visited a dervish lodge in preparation for our Rumi pilgrimage to Konya, and walking through Sufi tombs I naturally thought of the source of my own grief.

I often find that no other narrative form but poetry cuts straight through to the emotions and philosophical concepts I’m grappling with (and I think my mother agrees, based on her post about her favorite poets).

I’ve been writing poetry since I learned how to write, and it’s much more than a creative outlet for me. At age eight my mom gave me a “poetry album” with blank pages and since then I’ve let my mind roam in free verse and rhyme alike. I believe writing a poem is simpler than you think and just as powerful as therapy.

One of my favorite exercises that I like to do is to ask someone around me for a word, any word. Then on the spot I write a poem, whatever comes to mind, weaving that word in. I find that when reading my poem back over (unedited) I not just captured a fleeting moment, but got a deeper understanding of my current feelings.

So I encourage you to try that exercise. Ask someone around you to give you a word. Then find some stillness, a blank page, and a pen and play with that word. Find the words that unfold around it. Let that random word embrace who you are in this moment and put it to the page. Then perhaps share what you learned from it in the comment section below.

—

Getting back to the original question: Do I think I will ever see my best friend again? I think I see her every day, in my mind’s eye as she was. And in my heart as she is now; in the way only a dearly departed friend can remain.

I’m leaving you with this song that my beloved mother shared with me in the depths of my grief that still brings both a mixture of tears and solace when I hear it. It was written about a friend who suddenly passed on, and the words feel so true: “I always thought that I’d see you again.”

I just want to take this opportunity to declare my deep admiration and respect for these 2 great women, mother and daughter, it is remarkable the talent they possess, and the way they unfold in beautiful words and moving stories. It takes a real alchemical process to transform painful events into teachings and lessons of wisdom. That is the great power of choice we all have when we face a crisis. That is also why I have always loved Jean Paul Sartre's phrase: "Freedom is what we do with what is done to us".

Thank you for sharing your daughter with us, Amy. Marielle weaves her words so beautifully. I was quite touched. She reminded me that I, too, was pulled closer into spirituality after losing a loved one. My dad passed away in 2020 and strangely (beautifully) I feel closer to him now. I have a hard time saying that to my other family members who are grieving the loss still alongside me yet it feels true. Reading her words, I can tell Marielle carries her dear friend with her still.

And birds. I find myself watching them and wishing I had their view. Perhaps I should consider parasailing. 💕