The Improper Bohemians: Finding Love in Greenwich Village

In 1959 my parents fell in love the night they met, in a bar called Cafe Bohemia in Greenwich Village and on the very same night my father proposed. It's too good a love story not to share.

In the early spring of 1959 three young women from Lowell, Massachusetts were enjoying a weekend in New York City. After watching a matinee of the musical “West Side Story,” they made their way to Greenwich Village for drinks, settling on Cafe Bohemia at 15 Barrow Street where they perched on bar stools at round wooden tables, sipping their drinks. A young man’s gaze focused on the vivacious brunette in the trio. Before long, he sidled up to their table and began a conversation with my mother, Freda, that would become family lore through the generations.

“I couldn’t help but overhear that you were at the matinee of ‘West Side Story,’” he said.

My mother looked at him and nodded in assent.

My father Norman took that as an invitation to keep going. He was a slender, short, handsome man with a teasing smile. “Well, in today’s performance, something went wrong with the stage props and instead of a fake gun, when Chino shoots Tony, it was a real gun and they had to rush him to the hospital.”

My mother smiled. Having seen the performance, she was well aware that no such tragedy had taken place but she was inclined to humor Norman. They continued talking and after awhile he made an irresistible invitation.

“Do you want to hear Nina Simone tonight? She’s playing down the street,” he suggested.

Freda rose from the table and picked up her purse. Her friends were startled and concerned. She told them, “Anyone who makes up a story like that about ‘West Side Story’ has to be harmless. Don’t worry.”

And so began Norman and Freda’s first night together, one in which my father would eventually, several drinks later, suggest to Freda: “Why don’t we get married?”

My mother assured me and my siblings, and later her grandchildren when they heard the story of how their grandparents met, that she didn’t say yes right away.

Yet there was an inevitability about that fateful night.

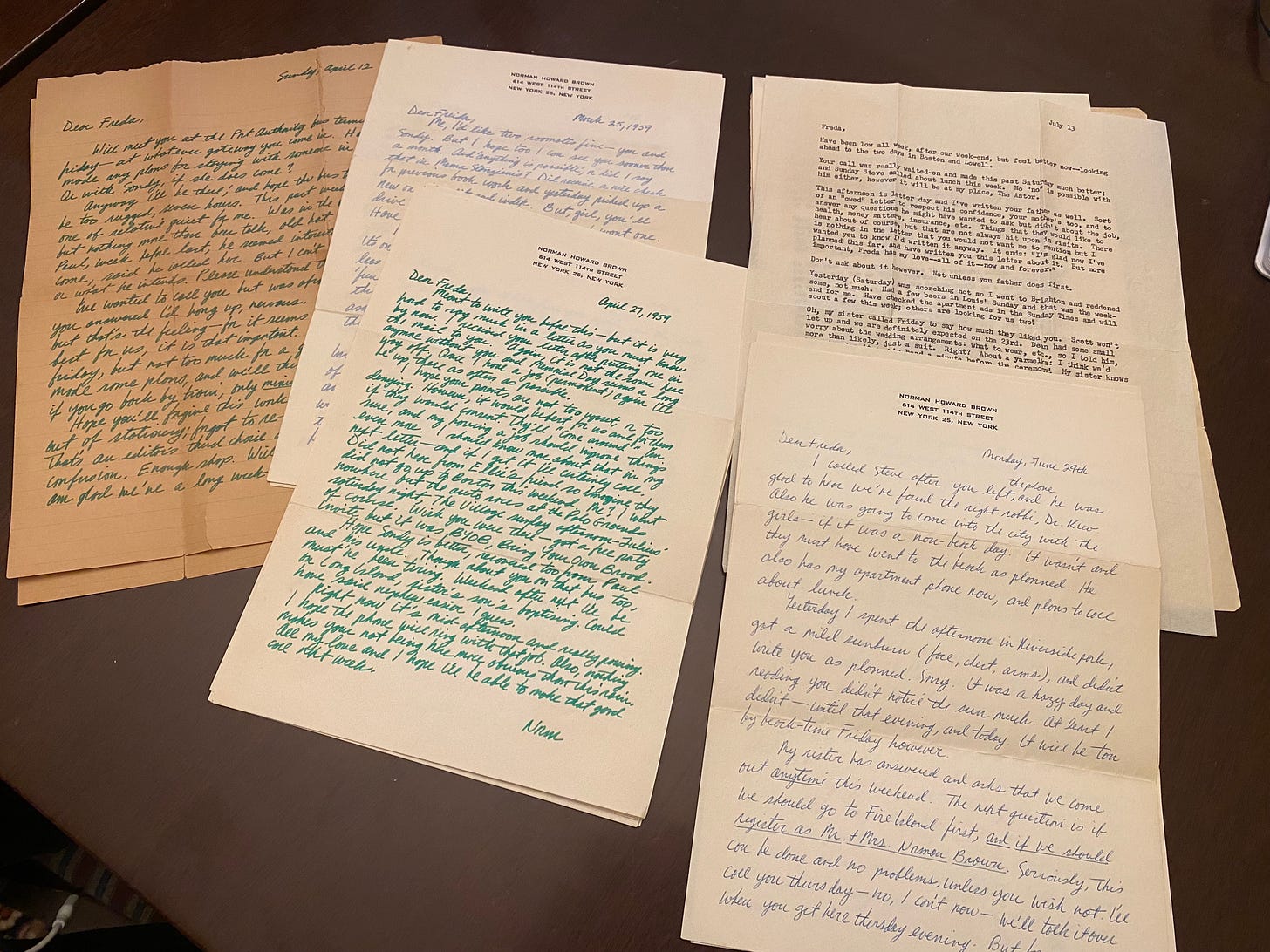

I know that because I am now in possession of the letters that my father wrote to my mother between March 1959 until just after my birth in April 1960. In reading these handwritten and occasionally typed letters, a story unfolds of a 29-year-old man from Patchogue, Long Island, a Korean War veteran attending Columbia University on the G.I bill, and the 22-year-old only daughter of doting parents in Lowell, a working-class mill city. He was Protestant. She was Jewish. There would be difficulties ahead. But Freda was a woman who knew what she wanted and Norman made her laugh.

From the first letters, in March and April 1959, my father begins to use the phrase that would be his incantation throughout the courtship. “Anything is possible,” he writes. In the weeks since Freda has gone back to Lowell and they are planning their next time together, his longing is palpable.

“The Village, though—it is much less without you to show it to, and share in that ‘fun for the whole family.’ And I have never felt this way before but realize now the things said, asked may have seemed to you rash or some such. They were deeply felt.”

My father, who would become a published author of two books and hundreds of articles, concludes: “I’m not much good with a pen but I do miss you already, very much. And this letter can only touch on what I feel. Read beyond the lines.”

I am reading beyond the lines as I write this essay sitting in a Hudson Street cafe in the heart of Greenwich Village’s Historic District. I walk the streets of this neighborhood on this early autumn day, the oak and linden trees still green-leafed against the brownstone apartment buildings and the wrought-iron fire escapes, and think about where Freda and Norman might have strolled holding hands, planning their future together. This Friday, Sept 27, marks their wedding anniversary. It’s another autumn in New York, sixty-five years later.

When Frank Sinatra sings, “Dreamers with empty hands” in “Autumn in New York,” I see my father scraping by on a freelance writer’s modest pay, promising my mother that it will all work out—he will get the good “career” job (“Girl, you’ll drive me to a steady job,” he writes), they will be able to persuade her skeptical parents that this non-Jew is worthy of their daughter. He will do what it takes—including converting to Judaism (which he does).

When he’s not planning their future, Norman reminisces about their favorite Village haunts, which includes Julius’, a bar that opened as a speakeasy during Prohibition, at the corner of Waverly Place and West 10th Street. By the 1950s, it was a famous gathering place for artists and writers. Toward the end of the decade, as LGBTQ+ life in the Village was moving from below Washington Square to the Christopher Street area, Julius’ began to attract gay men, who gathered there among its straight patrons. On April 21, 1966 it became famous for its “sip-in” protesting anti-gay discrimination in bars and other public places.

That my parents should have chosen as their favorite bar one that welcomed both gay and straight patrons is no surprise to me. My mother was fierce in her beliefs that every person deserves to be treated with the same respect and be granted the same basic human rights. She fought for justice her entire life. Several years ago my daughter Marielle and I brought my mother back to Julius. With a smile on her face, she strode right past the counter and into the furthest back corner of the bar. “This is where we used to sit,” she said. This past May, a few weeks after Mom’s death, I went to Julius’ on the first night of the Pride celebration with my daughter and friends. We danced to joyful, raucous disco songs in a packed bar, and I knew my parents were pumping their fists right alongside us.

The unlikely suitor

Meanwhile, in April 1959, my father’s letters chronicle his job interviews, his reasoning that they should live in New York City where he has job leads, and not Boston, which her parents would prefer. He pleads with Freda “come on down, and will show you what’s left of this town and Village—with you gone, it’s not the same.”

Finally, in a letter dated April 12, 1959 (a year before my birth), it seems their reunion is at hand, with my mother arriving in a few days to Port Authority bus terminal after a seven-hour trip from Lowell. My father confesses:

“I wanted to call you at home but was afraid that unless you answered I’d hang up, nervous. All stupid, I suppose, but that’s the feeling—for it seems I’ve got to have the best for us, it is that important.”

After a reunion that was “amazing and great,” my father gently inquires, “and how are your parents feeling now? Remember that they matter, as we do. Also remember that ‘anything is possible.’” He concludes: “Have to return to work now and that means putting you out of mind. It is difficult.”

By late April, as I read “beyond the lines” of my father’s letters, it’s clear there are intense discussions in the Lowell household around the suitability of this young man for their precious Freda.

“I hope your parents are not too upset or too denying. However, it would be best for us and for them if they would consent. They’ll ‘come around,’ I’m sure and my having a job should improve things even more.”

My father writes this letter from his bachelor pad on West 114th Street and I imagine him looking out the window with a sigh as he writes, “Right now it’s mid-afternoon and really pouring. Nothing makes you not being here more obvious than this rain.”

Good news on the job front arrives by early May. Norman has a second interview for a job at $90 a week as a technical writer for McGraw-Hill Book Co. Then his thoughts drift from the doer to the dreamer:

“Spent this afternoon, a warm one, in Riverside Park with The Times. Read some, the classifieds, news, book reviews and then just lay in the grass—in love, I guess.”

Back in Lowell, it seems my grandparents are softening towards Norman. He got the job with McGraw-Hill and he strikes an optimistic note: “Our future looks very bright right now, and we should be able to show your parents we really care soon.”

The “improper Bohemians”

Freda comes to New York City for Memorial Day weekend, and Norman suggests they rent bikes in Central Park “and move the legs, see the park.” This is a glorious vision. I hope they did. I don’t remember ever seeing my parents ride a bike, although they taught all three of their children to do so. I see my parents laughing, pedaling around Sheep’s Meadow.

In that same May letter, he refers to the reviewer of a book, The Improper Bohemians, that dedicated the New York Herald Tribune review to Julius’. “It’s tacked up on the phone booth now,” Norman reports.

I like the sound of that—the improper bohemians. It suits this love story. My parents both read On The Road by Jack Kerouac, a pioneer of the Beat Generation, the American counterculture movement that began in the 1940s. Freda and Norman would have been proud to be called bohemians and even more so—by dint of their unconventional marriage—improper ones. They gave birth to my own wanderlust:

By the end his May 17, 1959 letter my father’s optimism can’t be contained. “Now there’ll be no stopping us.” And indeed, his visit to my mother in Lowell and the meeting with her parents a month later went well. On his return to New York, he writes Freda “with memories of the wonderful weekend still fresh—even the rain couldn’t stop us…we have both gotten off on the best conditions possible. Your father is a fine and honest man; I think you could see that I felt that—as he felt your loss. Your mother; well, your mother is wonderful, listen to her.”

He reports that his summer suit wasn’t too warm on the bus ride back to New York City and promises: “Will bring a bag next time! And a toothbrush! And pajamas!” Already he is dealing with the practicalities of the marriage to his Jewish bride-to-be, including a meeting with the rabbi who will oversee his conversion. The September wedding is on the horizon.

“You know I love you, or what would we be doing making such plans together? Plans that we’ll realize very soon—but nowhere soon enough,” he writes at the end of June. He tells her of a letter he wrote my grandfather, becoming more explicit in his intentions about how he’ll support my mother. He re-reads my mother’s latest letter (how I wish I had them as well!) with her echoing optimism: “Just happy times from now on,” Freda wrote.

In Norman’s last letter of the summer, from August, there is talk of the honeymoon, of the upcoming wedding reception and his nerves (“Only hope that I ‘shape up’ for your friends, your parents’ friends”), and the second reception with friends in the city. He is apartment hunting in the Village and if no success, will look elsewhere “but not in Brooklyn, Bronx until all else is beyond hope.” He’s hoping for a monthly rent around $100-115.

I know that they end up with a place on the upper East Side, around 72nd Street—the apartment where I live for my first year until my mother decides the soot on her baby’s blanket from strolling Manhattan streets is no longer tolerable. A suburban childhood on Long Island is her vision, a plastic pool on a grassy lawn with a fenced-in yard, and so off they go. But that’s the next chapter of this story, for another day.

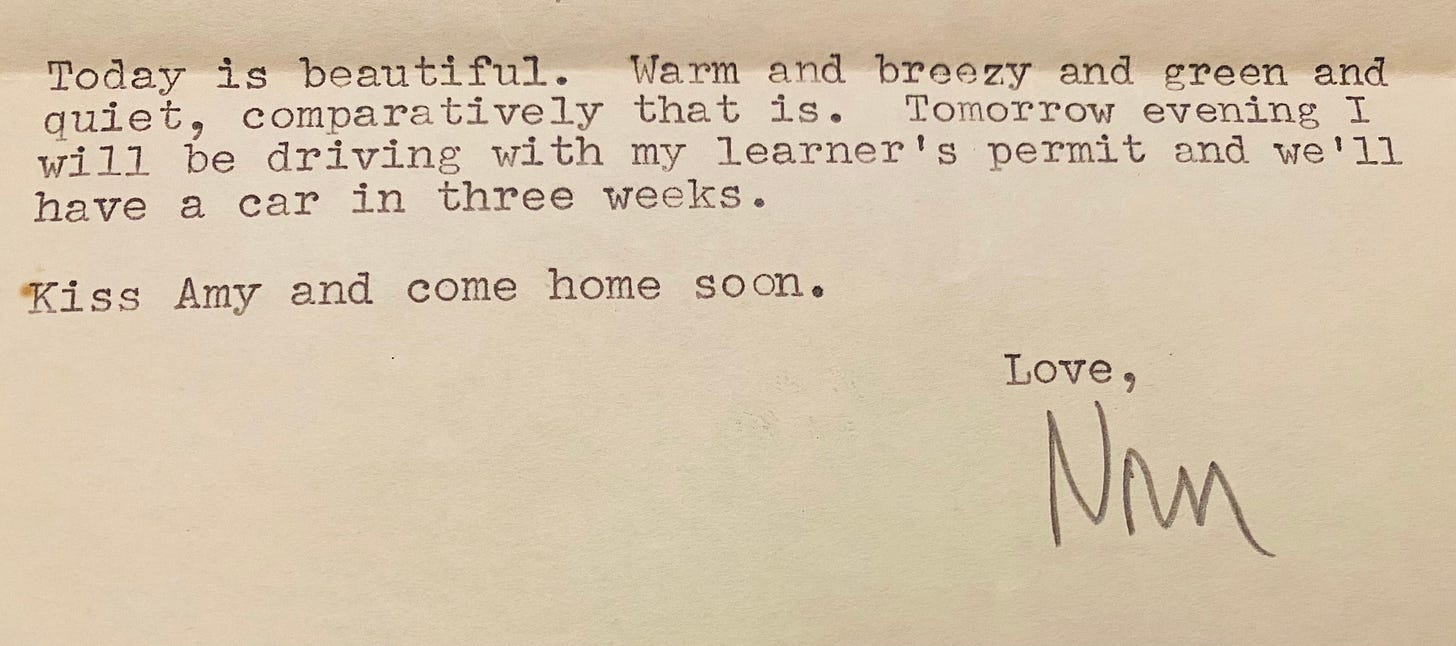

The final letter I have from my father is just the second page; the first is missing. It is not dated. But it has to be after April 1960 because he reports that the Davol Rubber Company has sent two free nipples and assorted booklets like “Baby Feeding Made Easier.” My mother must be visiting her parents in Lowell with her newborn. My father ends the letter:

“Today is beautiful. Warm and breezy and green and quiet, comparatively, that is. Tomorrow evening I will be driving with my learner’s permit and we’ll have a car in three weeks. Kiss Amy and come home soon.”

I look up from the table at the cafe where I’ve been lost in this 1959 courtship. An elderly woman is seated across from me, next to a woman who is clearly her caregiver. With a tremor in her hand, the woman, probably in her late 80s, lifts an avocado sandwich to her lips. She eats with concentration and when she’s done, there’s a satisfied burp. She looks up and smiles at me. “Excuse me,” she says. I smile back.

When I turn back to my laptop, my eyes brim. What was the last sandwich my mother enjoyed? I am trying to remember. All I can think of is her last days in her room at the memory care facility when she had no appetite, when she was ready at long last to join Norman, her one and only love for the 50 years of their marriage.

She would want me to think of that Freda and Norman, the young and brave lovers who defied convention, religious differences and parental reservations to follow the path of their destiny together. That is how she would want to be remembered.

And so I raise a glass on this fine New York September day to my parents and to all dreamers, everywhere.

LET’S CHAT! A question for the comments:

Is there a love story that inspires you? I’d enjoy hearing about it. This is a safe place to share. Did you know if you click the Comment button below or little heart ❤️ at the top or bottom of this newsletter each week, it makes it easier for people to find their way here? (If you read it in your inbox, click on the heart or button below to come to my Substack page). I read and respond to every comment.

Welcome the many new subscribers. I am delighted you are here! If you haven’t already, please visit my Welcome page and leave a comment introducing yourself. What brought you to Living in 3D? What kind of multiple-dimensioned life are you living? What topics would you like to see me explore here?

I’ll leave you with some of my parents’ favorite songs, A New York Love Story playlist. Enjoy! And next week look for Part 2 of “Walking Myself Home on the Camino de Santiago.” Read Part 1 here.

I'm late to your post, but loved reading about Freda and Norman, their origin story and their early years--wonderful! Love that you took your mom back to Julius' and that you returned there for Pride. My parents met around the same time yours did, though not in nearly so interesting a way: they met at a frat party at the University of Missouri. My dad had gone to the party with someone else, but left the party with my mom....

Wow. Wonderful voice and storytelling, Amy!